Planning Mortar: Six Steps to Laying a Strong Foundation

As I was re-reading Rethinking English Language Instruction: An Architectural Approach by Susana Dutro and Carrol Moran, I was reminded of the importance of identifying mortar words when setting language goals. Knowing how to teach mortar words is really tricky. Since good teaching always starts with careful planning, this first post about mortar words helps teachers identify what to teach first. Here are six steps to planning and laying a strong foundation. I will elaborate on steps 5 and 6 in a separate post (see Mortar Words: Connecting the Bricks).

A Quick Review of Bricks and Mortar

Dutro & Moran (2003) distinguish between two types of vocabulary words:

“Brick” words are the important or key words, those that are bold-faced in a text or could be found in a glossary. We often refer to those as content-specific words. If we were studying the Solar System, “brick” words would include: sun, planet, moon, rotation, solar system, star, comet, Milky Way…)

“Mortar” words are utility words required to construct sentences. They connect and strengthen brick words. Mortar words include:

- Connecting words required to construct complex sentences: because, sometimes, therefore, however, whereas, etc.

- Prepositions and prepositional phrases: in, on, under, behind, next to, in front of, etc.

- Basic regular and irregular verbs: leave, live, eat, use, etc.

- Pronouns and pronominal phrases: she, his, their, it, us, each other, themselves

- General academic vocabulary: notice, think, analyze, direct, plan, compare, proof, survive, characteristics

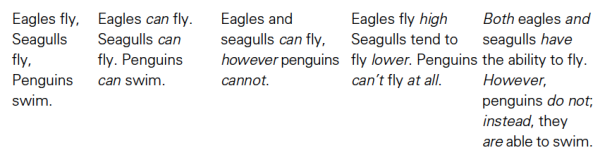

Mortar words present both the gift and predicament of differentiating an intermediate from a fluent speaker. The ability to use more advanced mortar words shows deeper conceptual understanding in discussions and in writing. Let’s take the following example presented by Dutro and Moran (2003). The left column presents utterances by a beginner speaker whilst the right column shows an advanced speaker. Notice how the word both, however and instead create the nuances of comparison and contrast. The words eagle, fly, seagulls, penguins and swim (all brick words) do not equip students to demonstrate this depth of understanding.

Six Steps to Laying a Strong Foundation

So how do you make sure you teach both bricks and mortar words?

1. Determine the language function. What type of final product will your students be producing for this unit? What will be the purpose of their writing? Is it to ask and answer questions, compare and contrast, explain cause and effect, persuade, draw conclusions, infer, summarize, communicate research findings, describe, narrate…?

2. Identify the grammatical forms needed to show a higher level of proficiency. What verb tenses do they need for this task? What rules of subject/verb agreement should they use? What sentence structures will identify their work as a step above? How can students vary subjects in sentences (use of pronouns)?

3. Make a list of brick words (content-specific vocabulary). What are the key words that they need for this unit? Are there some that are more advanced than others? What will be pre-taught and what will be taught explicitly throughout?

4. Make a short list of mortar words (connecting words and more general academic vocabulary). When I write more complex sentences for this function, what types of words keep coming up? What would be the most appropriate transition words to teach at this time?

5. Plan for explicit instruction. Identify those forms in shared reading. Model the use of these forms during minilessons. Engage students in co-authoring a text during shared writing. Create charts for students to refer to where mortar words are highlighted in sentences and paragraphs.

6. Hold students accountable for those forms. Provide opportunities for students to use those words authentically. Include these forms as part of your assessment rubrics. Create personal checklists for students to verify that they are using all of the structures taught.

TIP: Less is more. It is easier to remember and use brick words than mortar words. Choose fewer mortar words to ensure a more solid binding. 🙂

Dutro, S. & Moran, C. (2003) Rethinking English language instruction: An architectural approach. In Garcia, G. (Ed.) English learners: Reaching the highest level of English literacy, pp. 227-258. Newark, DE: IRA.

Recent comments